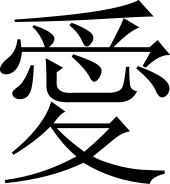

Love

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Love (disambiguation).

Archetypal lovers Romeo and Juliet portrayed by Frank Dicksee

An illustration of the unconditional love between a little girl and her dog.

Love is an emotion of strong affection and personal attachment.[1] In philosophical context, love is a virtue representing all of human kindness, compassion, and affection. Love is central to many religions, as in the Christian phrase, "God is love" or Agape in the Canonical gospels.[2] Love may also be described as actions towards others (or oneself) based on compassion.[3] Or as actions towards others based on affection.[3]

Love is an emotion of strong affection and personal attachment.[1] In philosophical context, love is a virtue representing all of human kindness, compassion, and affection. Love is central to many religions, as in the Christian phrase, "God is love" or Agape in the Canonical gospels.[2] Love may also be described as actions towards others (or oneself) based on compassion.[3] Or as actions towards others based on affection.[3]In English, the word love can refer to a variety of different feelings, states, and attitudes, ranging from generic pleasure ("I loved that meal") to intense interpersonal attraction ("I love my partner"). "Love" can also refer specifically to the passionate desire and intimacy of romantic love, to the sexual love of eros (cf. Greek words for love), to the emotional closeness of familial love, or to the platonic love that defines friendship,[4] to the profound oneness or devotion of religious love.[5] This diversity of uses and meanings, combined with the complexity of the feelings involved, makes love unusually difficult to consistently define, even compared to other emotional states.

Love in its various forms acts as a major facilitator of interpersonal relationships and, owing to its central psychological importance, is one of the most common themes in the creative arts.

Helen Fisher defines what could be understood as love as an evolved state of the survival instinct, primarily used to keep human beings together against menaces and to facilitate the continuation of the species through reproduction.[6]